When you pick up a prescription, you might not realize that the difference between a brand-name pill and its generic version could save your state hundreds of millions of dollars a year. That’s not magic-it’s policy. Across the U.S., states have quietly built a system of financial nudges and legal rules designed to push doctors, pharmacists, and patients toward cheaper generic drugs. These aren’t just suggestions. They’re structured incentives-some subtle, some strict-that shape what gets dispensed, what you pay at the counter, and even whether a pharmacist can swap a brand drug for a generic without asking you first.

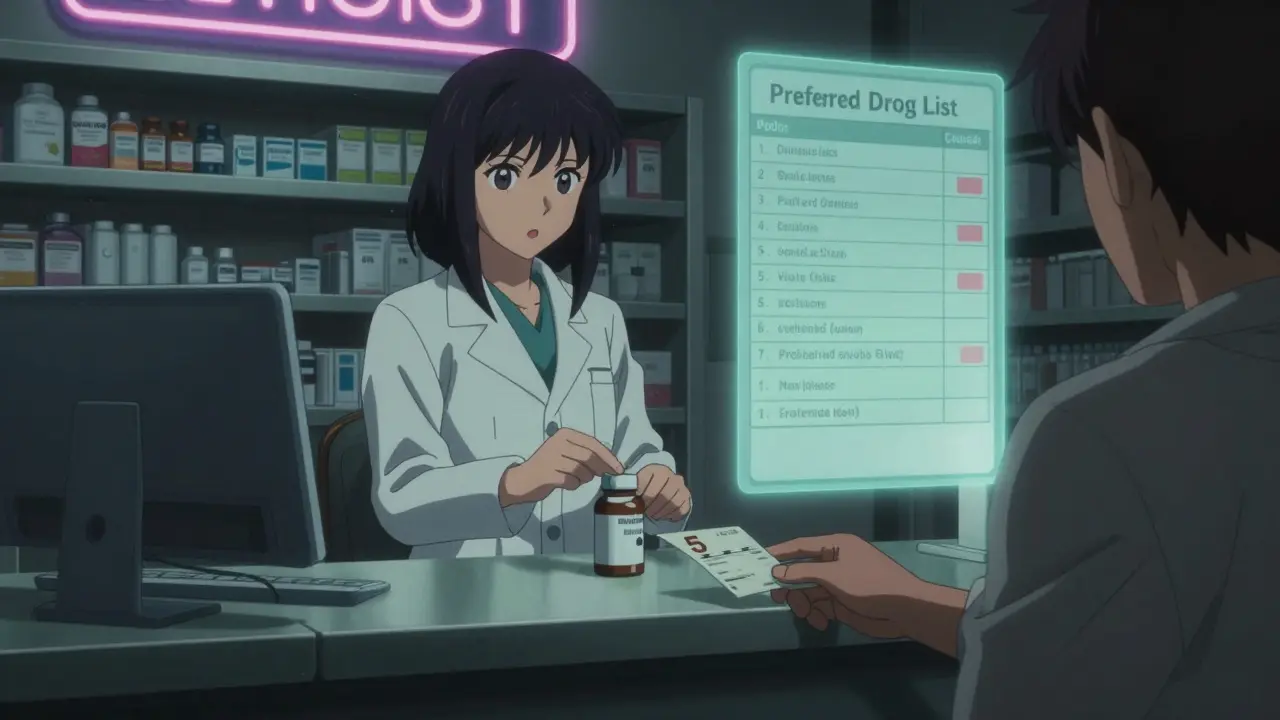

How States Push for Generics Without Banning Brands

States don’t outlaw brand-name drugs. That would be illegal and unpopular. Instead, they make generics the easier, cheaper choice. The most common tool? Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). As of 2019, 46 out of 50 states used these lists to control what gets covered under Medicaid. If a drug isn’t on the list, your doctor has to jump through hoops to get it approved-often with paperwork, prior authorization, or even a phone call. Meanwhile, drugs on the list? Covered with little to no hassle.PDLs work because they’re tied to money. States negotiate rebates with drugmakers, sometimes getting extra cash back if they favor certain generics. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, started in 1990, forces manufacturers to pay at least 13% of the drug’s price back to the state. But many states go further, squeezing out even bigger discounts by making generics the default option. In 29 states, a committee of pharmacists and doctors decides which drugs make the list. In others, it’s the Medicaid agency itself. Either way, the goal is the same: steer prescriptions toward the lowest-cost option that still works.

Why Your Copay Might Be $5 for Generic and $40 for Brand

You’ve probably seen it: a $5 copay for a generic blood pressure pill, and $40 for the brand version. That’s not a mistake. It’s intentional. States use copayment differentials to make the financial choice obvious. The bigger the gap, the more likely you are to pick the generic.This isn’t new. Back in the late 1990s, the difference between what pharmacies earned dispensing a brand vs. generic drug was barely eight cents. But copay differences kept growing. Why? Because states realized that if patients feel the pain at the register, they’ll choose the cheaper option-even if the doctor doesn’t change the prescription.

Studies show it works. A 2018 NIH study found that when patients pay more for brand-name drugs, they switch to generics at higher rates. One estimate said if every state had a $3 higher copay for brand drugs, generic use would jump enough to save $51 billion a year. That’s not theoretical. It’s happening in real clinics, real pharmacies, and real patients’ wallets.

The Silent Switch: Presumed Consent vs. Explicit Consent

Here’s something most people don’t know: your pharmacist might already be swapping your brand drug for a generic-without telling you. That’s because of presumed consent laws. In 11 states, pharmacists can substitute a generic unless you specifically say no. In the other 39, they need your explicit permission.That small difference has a huge impact. The same NIH study found that presumed consent laws increased generic dispensing by 3.2 percentage points. That might sound small, but multiply that across millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking billions in savings. In states with explicit consent, pharmacists still substitute generics-but only about half the time. Why? Because asking for permission slows things down. And pharmacists, like everyone else, prefer efficiency.

Here’s the twist: mandatory substitution laws-where pharmacists have to switch-don’t work nearly as well. Why? Because pharmacists already have a financial reason to dispense generics. They make more profit on them. So forcing them doesn’t change behavior much. But giving patients a financial reason to accept the switch? That changes everything.

How 340B and Medicare Influence State Decisions

It’s not just Medicaid driving this. The 340B Drug Pricing Program, created in 1992, lets safety-net hospitals and clinics buy drugs at steep discounts-often 20% to 50% off. These places are required to use those savings to help low-income patients. So naturally, they push generics even harder. A clinic serving uninsured patients isn’t going to waste money on a $200 brand-name drug when a $15 generic does the same job.And now, the federal government is watching. CMS-the agency that runs Medicare-is testing a new idea called the $2 Drug List Model. It’s simple: for certain low-cost generics, patients pay just $2, no matter what their plan says. It’s a pilot, but if it works, states might copy it. Why? Because it removes confusion. No more wondering if your copay is $5, $10, or $20. Just $2. That kind of clarity makes patients more likely to stick with generics.

Why Some Generic Drugs Disappear from Shelves

Here’s the dark side: sometimes, the very systems meant to save money end up hurting generic availability. Generic manufacturers rely on Medicaid rebates to stay profitable. But if their drug’s price drops too much-because of competition, a shortage, or a change in manufacturing costs-they can end up owing more in rebates than they make on sales.Avalere Health found five scenarios where this happens. One: if a drug’s price drops because a competitor enters the market, the manufacturer still has to pay a rebate based on the old, higher price. Two: if the cost of ingredients goes up but the drug’s price doesn’t, the rebate still applies. Three: if the drug is used less than expected, the rebate doesn’t shrink. In all these cases, the manufacturer loses money. And when they lose money, they stop making the drug.

That’s not a glitch. It’s a design flaw. States want low prices. But if the price drops too far, the generic disappears. Then patients are stuck with expensive brand-name alternatives-or no option at all. It’s a classic unintended consequence: the policy works too well, and breaks the market.

What’s Working-and What’s Not

So what’s the best way to get more generics into patients’ hands? The evidence points to one clear winner: patient-facing financial incentives. Copay differentials, the $2 drug list, presumed consent-all of these put the choice in the patient’s hands, and make the cost real at the moment of decision.Provider-focused tools-like telling doctors to prescribe generics-don’t work as well. Doctors already know generics are cheaper. But they’re not always the ones paying. Patients are. And patients respond to price.

Meanwhile, mandatory substitution laws? They’re mostly useless. Pharmacists are already substituting generics because it’s profitable. They don’t need a law to do it. But they do need patients to say yes. And that’s where presumed consent helps.

The real winners are states that combine three things: a strong Preferred Drug List, a wide copay gap between brand and generic, and presumed consent laws. Together, they create a system where the cheapest, safest option is also the easiest one.

What Comes Next?

States aren’t done. With drug prices still climbing and Medicaid budgets stretched thin, the pressure to cut costs will only grow. More states will likely adopt presumed consent laws. More will experiment with flat $2 or $5 copays for generics. And some may start linking generic use to provider bonuses-though that’s still rare.The federal $2 Drug List Model could become a blueprint. If it proves successful, states might adopt it for Medicaid too. That would mean a nationwide standard for low-cost generics-something that’s been missing for decades.

But the biggest challenge isn’t policy. It’s sustainability. If we keep pushing prices down without protecting manufacturers, we’ll end up with fewer generic options. The goal isn’t just to save money today. It’s to make sure the next generic drug is still there tomorrow.

Kevin Lopez

December 29, 2025 AT 02:42Preferred Drug Lists are just cost-shifting disguised as efficiency. You're not saving money-you're creating access barriers for chronic patients who need brand-name stability. The NIH data ignores adherence drops. If your BP med switches every quarter, you're not saving $51B-you're increasing ER visits. This isn't policy. It's rationing by spreadsheet.

Teresa Rodriguez leon

December 30, 2025 AT 20:09I’ve been on the same brand for 8 years. My body freaks out when they swap it. No one ever asks. I just show up with a $40 bill and cry in the parking lot. This system doesn’t care about people. It cares about numbers.

Manan Pandya

December 31, 2025 AT 22:22The structural incentives described here are a textbook example of behavioral economics applied effectively. Copay differentials leverage loss aversion, while presumed consent reduces decision fatigue. The key insight is that patient autonomy is preserved, yet nudged toward economically rational outcomes. This is not coercion-it’s enlightened default design.

Emma Duquemin

January 1, 2026 AT 20:53OH MY GOD. I JUST REALIZED WHY MY PHARMACIST LOOKS AT ME LIKE I’M A LOST PUPPY WHEN I ASK FOR THE BRAND. IT’S NOT BECAUSE I’M WEIRD-IT’S BECAUSE I’M THE 3% WHO STILL ASK. I’VE BEEN PAYING $40 FOR A DRUG THAT COSTS $1.25 TO MAKE AND I THOUGHT I WAS BEING LOYAL. I’M SO MAD. AND ALSO KIND OF IN LOVE WITH THIS SYSTEM NOW. THANK YOU FOR THIS EYE-OPENER. I’M SWITCHING TO GENERIC TOMORROW. AND I’M TELLING EVERYONE.

Duncan Careless

January 3, 2026 AT 17:41interesting read. i wasnt aware of the presumed consent thing. kinda scary, right? like, you dont even know youre being swapped out. but then again, i guess if it saves money and the med works the same… maybe its fine? not sure. just feels weird. also, typo in the article: 'pharmacist can swap a brand drug for a generic without asking you first' - should be 'without asking YOU first'. just sayin.

Samar Khan

January 5, 2026 AT 02:23so like… this whole system is just making poor people take drugs they don’t want because the state says so? 😭 and then when the generic disappears? 😭😭😭 i’m crying. why do we do this to each other? 💔💸 #genericcrisis #pharmabusinessisawful

Jasmine Yule

January 5, 2026 AT 03:36People act like this is some evil conspiracy but let’s be real - if you’re paying $40 for a pill that’s chemically identical to a $5 one, you’re literally funding corporate greed. The system isn’t broken - it’s working exactly as designed. The problem is we’ve let drug companies turn medicine into a casino. Stop crying about your brand loyalty and start asking why your insulin costs more than your rent.

Greg Quinn

January 5, 2026 AT 19:29It’s fascinating how policy can be so invisible yet so powerful. We don’t notice the architecture of our choices until someone points it out. The real question isn’t whether this works - it’s whether we’re comfortable letting financial incentives determine health outcomes. What happens when the ‘cheapest’ option isn’t the ‘best’ for a human being? We’ve built a machine that optimizes for cost, not care.

Alex Ronald

January 7, 2026 AT 12:55Just wanted to add - if you’re in a 340B clinic, they’re already doing this right. No copays, no hassle, just generics because they know what works and what doesn’t. It’s not about forcing people - it’s about removing barriers. We’ve seen adherence go up 40% since switching to default generics. It’s not magic. It’s just common sense.

Amy Cannon

January 9, 2026 AT 01:38It is of the utmost importance to recognize that the structural mechanisms delineated within this comprehensive exposition constitute a paradigmatic exemplar of state-level fiscal stewardship in the domain of pharmaceutical expenditure. The confluence of preferred drug lists, differential copay structures, and presumed consent protocols represents not merely an administrative innovation, but a moral imperative in the context of escalating healthcare expenditures and the ethical obligation to ensure equitable access to therapeutics for the most vulnerable populations. The unintended consequence of generic discontinuation, however, must be addressed with urgent regulatory recalibration to prevent market collapse and ensure sustained availability - for the sake of public health and the sanctity of the physician-patient relationship.

Himanshu Singh

January 10, 2026 AT 16:48good stuff! i didnt know about the 340b program, that’s so cool how clinics use it to help poor folks. also, i think the $2 drug list is the future. just make it simple. $2. done. no more confusion. maybe make it $1? 😆

Aliza Efraimov

January 12, 2026 AT 01:39Wait - you’re telling me pharmacists are already swapping my meds without asking? That’s not just legal - that’s terrifying. I’ve had bad reactions to generics before. My anxiety meds? Not interchangeable. My doctor wrote ‘Do Not Substitute’ on the script. But guess what? The pharmacy still tried. I had to call them three times. This isn’t efficiency - it’s negligence. States need to enforce ‘Do Not Substitute’ like it’s a law. Because for some of us, it is.