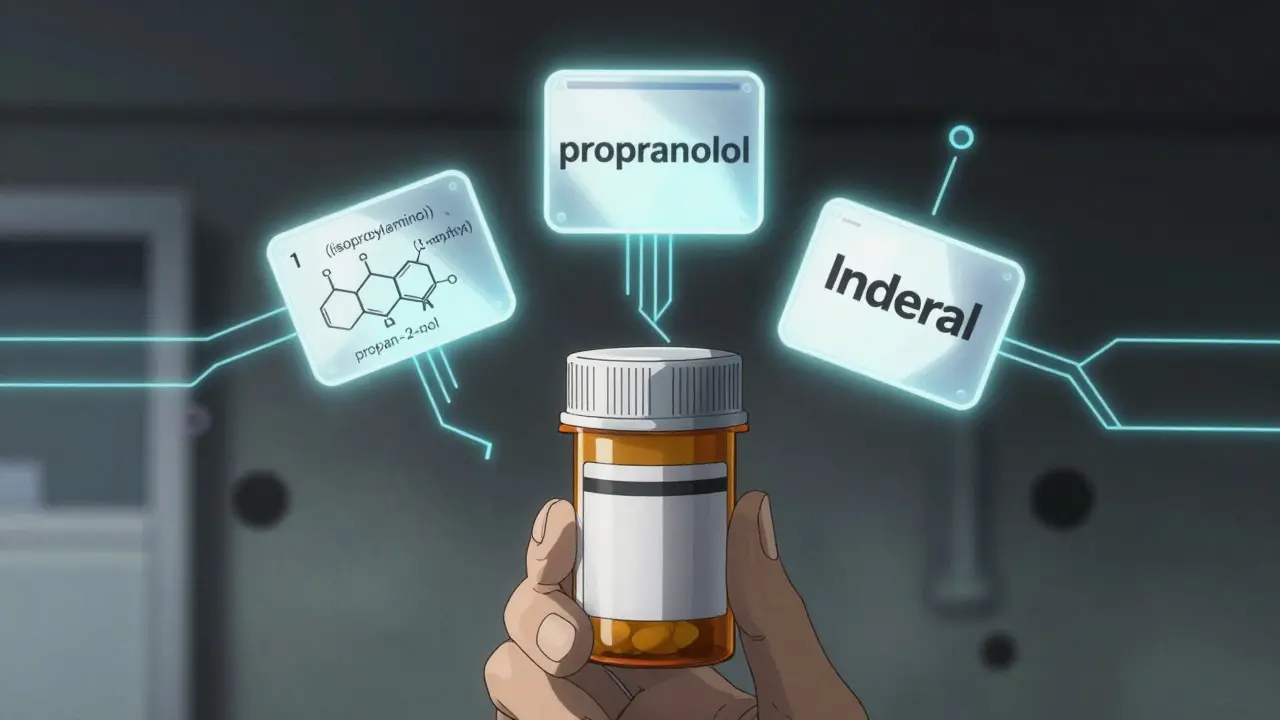

Have you ever looked at a prescription and wondered why a drug has three different names? You might see propranolol on the label, but your pharmacist hands you a pill with Inderal printed on it. And if you dig deeper, you’ll find a long, unpronounceable string like 1-(isopropylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy) propan-2-ol. It’s confusing - and it’s supposed to be. This isn’t marketing magic. It’s science, regulation, and safety working together.

Why Drugs Have Three Names

Every drug has a chemical name, a generic name, and a brand name. Each serves a different purpose. The chemical name tells you exactly what the molecule looks like. The generic name tells doctors and pharmacists what the drug does and what class it belongs to. The brand name is what the company uses to sell it. Together, they keep patients safe and medications clear - even across borders.

The system wasn’t always this organized. Before the 1950s, the same drug could have dozens of names depending on the country or manufacturer. A patient in Germany might get one version, while someone in Japan got another - with no way to tell if they were the same thing. That led to dangerous mix-ups. In 1953, the World Health Organization stepped in and launched the International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Programme. Today, over 10,000 drugs have standardized generic names approved by this system.

Chemical Names: The Molecular Blueprint

Chemical names are built using rules from the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). These names are precise. They describe every atom, bond, and group in the molecule. For example, the chemical name for propranolol is 1-(isopropylamino)-3-(1-naphthyloxy) propan-2-ol. That’s 50 characters long. Try saying that out loud during an emergency.

These names are for chemists and researchers. They’re not meant for prescriptions, labels, or conversations with patients. You won’t find them on a pill bottle. But they’re critical for drug development. When a new compound is synthesized in a lab, this is how scientists identify it before it even gets a generic name.

Think of it like a car’s VIN number. It’s not what you call the car at the gas station - but it’s the only way to know exactly which engine, transmission, and chassis it has. Same with drugs.

Generic Names: The Safety Code

This is where things get smart. Generic names aren’t random. They follow patterns. And those patterns save lives.

Take the suffixes - they tell you the drug’s class. If a drug ends in -prazole, like omeprazole or pantoprazole, it’s a proton pump inhibitor used for acid reflux. If it ends in -tinib, like imatinib or sunitinib, it’s a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used in cancer treatment. If it ends in -mab, like adalimumab or rituximab, it’s a monoclonal antibody.

The prefix? That’s what makes each drug unique. Ome-prazole, Lanso-prazole, Panto-prazole - all different drugs, same job. The USAN Council and WHO’s INN committee spend months testing these names. About 30% of proposed generic names get rejected because they sound too similar to existing ones. A single misheard name can lead to a deadly mistake.

Dr. Robert M. Goggin, former head of the USAN Council, found that properly structured generic names reduce medication errors by 27%. That’s not a small number. In the U.S. alone, over 1.5 million preventable drug errors happen every year. Standardized naming cuts that risk.

And it’s global. An INN name like metformin is used in the U.S., India, Brazil, and South Africa. A pharmacist in Lagos can recognize it the same way a pharmacist in London does. That’s why WHO tracks over 200 new generic names each year.

Brand Names: The Marketing Mask

Now comes the part you see on TV ads. Brand names - like Glucophage for metformin or Viagra for sildenafil - are chosen by pharmaceutical companies. They’re catchy. Memorable. Sometimes even clever.

But they’re also heavily regulated. Before a company can launch a drug, it submits 150-200 potential brand names to the FDA. About one in three get rejected. Why? Because “Zyloprim” sounds too much like “Zyprexa”. Or because “Vasotec” could be confused with “Vasotec” - wait, that’s the same name. That’s exactly the problem. The FDA checks spelling, sound, and even how it looks handwritten.

Brand names can’t claim疗效 (effectiveness). You won’t see “Blood Pressure Miracle” on a label. And every ad must include the generic name in small print. That’s not a loophole - it’s a safety rule.

Here’s something most people don’t know: brand and generic drugs contain the exact same active ingredient. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 made that law. But the pill’s color, shape, or flavor might be different. That’s why some patients get confused. They’ve always taken the blue pill. Now it’s white. They think it’s not the same. It is. But the packaging looks different - and that’s caused over 300 reported medication errors in 2022 alone.

Company Codes: The Lab Name

Before a drug has any of these names, it has a code. Pfizer uses PF-04965842-01. Roche uses RO-4995175. These aren’t marketing tools. They’re internal IDs. The numbers track the exact chemical structure, salt form, and batch. During clinical trials, scientists refer to the drug by this code. It’s the only way to be sure they’re testing the right molecule.

These codes can be long - up to 12 characters. But they’re precise. No room for error. When a drug finally gets its generic name, the company code is retired. But it lives on in research papers and regulatory files.

How the System Evolves

Drug development isn’t standing still. New types of medicines need new naming rules.

In 2023, the WHO introduced new stems for RNA-based therapies - they end in -siran. Peptide-drug conjugates now use -dutide. And targeted protein degraders, a growing class of cancer drugs, will soon use -tecan.

Technology is helping too. Since 2021, the USAN Council uses AI to scan 15,000 existing drug names in seconds. It checks for similar sounds, spellings, and even how they might be misread in handwriting. The system cut potential naming conflicts by 42% in its first year.

And it’s working. Since 2010, global medication errors linked to naming confusion have dropped by 18.5%. That’s thanks to standardization - not luck.

Why This Matters to You

If you take medication, this system protects you. It helps your pharmacist verify your prescription. It lets your doctor know exactly what you’re on - even if you’re traveling abroad. It prevents mix-ups between drugs that sound alike.

But it’s not perfect. A 2022 FDA survey found that 68% of patients find generic names confusing. Names like tofacitinib or abrocitinib are hard to pronounce. That’s why pharmacists and doctors need to explain them. Don’t be afraid to ask: “What’s this drug for?” or “Why does it have such a strange name?”

And if you’re switching from a brand to a generic? Know this: the active ingredient is identical. The difference is in the filler - the color, the shape, the flavor. Not the effect. If you feel different after switching, talk to your provider. But don’t assume it’s because the drug isn’t the same.

What’s Next

The future of drug names is getting more complex. With gene therapies, cell therapies, and personalized medicines on the rise, naming conventions will need to adapt. The FDA now requires every new drug application to include a full nomenclature risk report - analyzing 12 linguistic dimensions to prevent confusion.

As of 2023, over 14% of new drugs are advanced therapies - things like CAR-T cells or mRNA vaccines. These don’t fit neatly into the old -prazole or -mab patterns. New stems are being tested. New rules are being written.

One thing won’t change: the goal. Every name, whether chemical, generic, or brand, is designed with one thing in mind - patient safety. Not profit. Not branding. Not convenience. Safety.

Patrick Merrell

January 26, 2026 AT 17:42This system is a godsend. I've seen people die because they confused metformin with metoprolol. No joke. The generic naming convention isn't just convenient-it's lifesaving. Anyone who thinks this is bureaucratic nonsense has never held a dying patient's hand while their meds were mixed up.

SWAPNIL SIDAM

January 28, 2026 AT 07:29Wow! I never knew drugs had so many names. In India, we just call it by the brand. But now I see why this matters. My aunt took the wrong medicine once because the label looked similar. This is important. Thank you for explaining.

Nicholas Miter

January 29, 2026 AT 08:09Yeah, I used to think brand names were just marketing fluff. But after my kid had an allergic reaction to a generic version with a different filler (not the active ingredient, thankfully), I started paying attention. The color change freaked me out until I read up on it. Turns out, the FDA’s got your back more than you think.

Suresh Kumar Govindan

January 29, 2026 AT 08:57The WHO’s INN program is a façade. Corporate lobbying dictates naming conventions under the guise of safety. The real motive? Monopolistic control. Why else would 30% of proposed names be rejected-not for safety, but to favor established players? The system is rigged.

Aishah Bango

January 30, 2026 AT 00:22It’s wild how much thought goes into this. I used to think drug names were just random letters thrown together. Now I see how every syllable is a tiny shield against death. I wish more people knew this. Maybe then they wouldn’t panic when their blue pill turns white.

Angie Thompson

January 30, 2026 AT 11:45OMG I just learned that -mab means monoclonal antibody?? 😱 I’ve been taking adalimumab for years and never knew what it meant! Now I feel like a total science nerd. Also, why is it called ‘Vasotec’ and not ‘BloodPressureButBetter’? 😂 I’m telling my mom this at dinner tonight. She thinks generics are ‘fake medicine’.

Geoff Miskinis

February 1, 2026 AT 11:10Let’s be honest: the entire naming framework is a product of Anglo-American hegemony. Why should ‘propranolol’ be the global standard when it’s derived from a British chemical taxonomy? India and China have their own naming traditions-suppressed for ‘standardization.’ This isn’t safety. It’s cultural erasure.

Sally Dalton

February 2, 2026 AT 21:03I love how this post explains things so clearly! I work in a pharmacy and see people confused all the time-especially when switching from brand to generic. I always tell them: ‘Same medicine, different wrapper.’ And I show them the FDA’s website. It’s crazy how much fear comes from just a different color pill 💙

Betty Bomber

February 3, 2026 AT 12:03My dad’s on metformin. He still calls it ‘Glucophage’ even though it’s been generic for 15 years. I think he just likes the way it sounds. Funny how names stick, huh?

Mohammed Rizvi

February 5, 2026 AT 10:43So let me get this straight-you’re telling me the same pill that costs $150 under ‘Viagra’ is literally identical to the $3 generic? And the only difference is the color and the logo? 😏 Guess that’s why Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know. But hey, at least the name ‘sildenafil’ sounds like a rejected Marvel villain. Cool.