AGEP Diagnostic Probability Calculator

Diagnose AGEP Risk

This tool estimates the probability of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis based on clinical criteria from the EuroSCAR diagnostic scoring system. Not a medical diagnosis.

Results will appear here after calculation

AGEP is not a common condition, but when it hits, it hits fast. Imagine waking up with your skin covered in tiny white pustules-like pinpricks of pus-on a red, fiery base. Within hours, it spreads from your armpits and groin to your chest, face, and limbs. You might have a fever. Your skin feels hot and tender. You feel awful. And you didn’t do anything wrong. This isn’t an infection. It’s not allergies in the usual sense. It’s Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis, or AGEP-a severe, drug-triggered reaction that can turn your body into a warning sign.

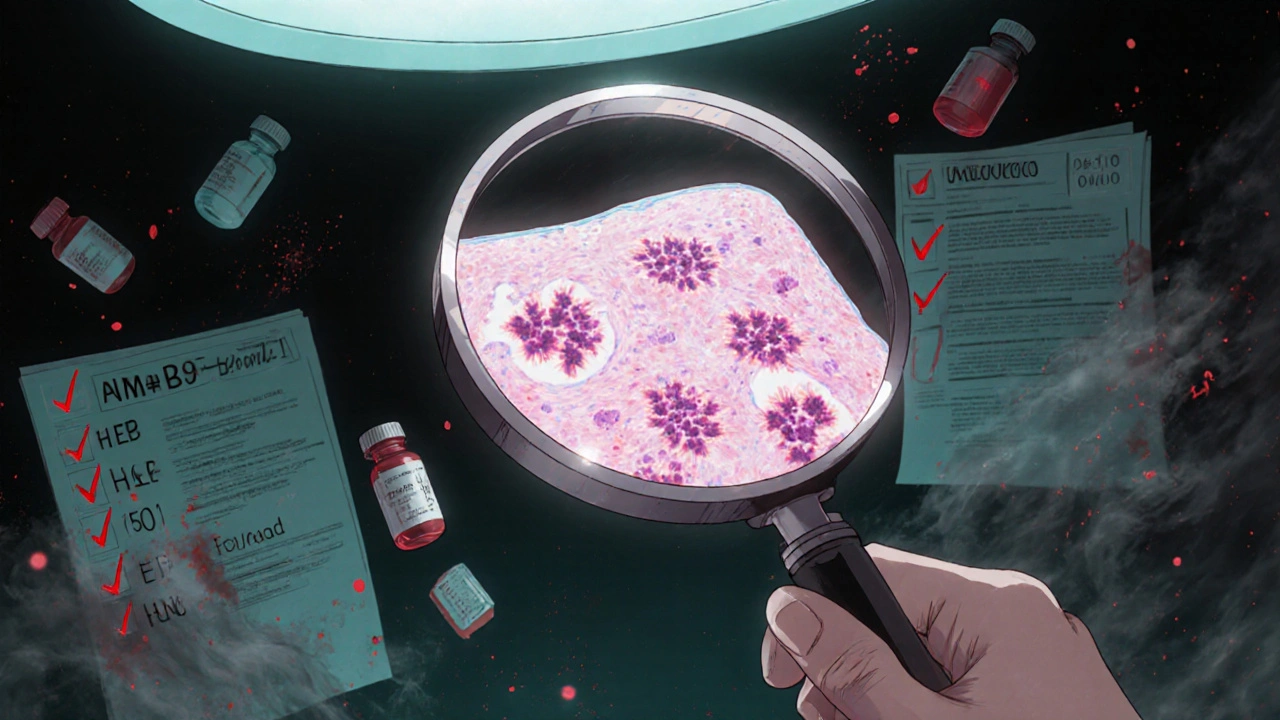

What Does AGEP Actually Look Like?

AGEP doesn’t start slowly. It shows up within 1 to 5 days after taking a new medication-often as soon as 24 hours. The first spots are small, sterile pustules, about 1 to 2 millimeters wide. They don’t form around hair follicles like acne. They just pop up randomly on red, swollen skin. You’ll usually notice them first in skin folds: under your arms, in your groin, or behind your knees. Then, within a day or two, they spread everywhere.

Unlike psoriasis or infections, AGEP pustules aren’t filled with bacteria. They’re packed with white blood cells-mostly neutrophils-your body’s first responders. The skin underneath is inflamed, swollen, and tender. Many patients also have a fever above 38.5°C, feel tired, and have swollen lymph nodes. Blood tests almost always show high white blood cell counts, especially neutrophils, and elevated CRP, a marker of inflammation.

One key clue that helps doctors tell AGEP apart from other rashes? The pustules don’t turn into blisters or break open easily. And unlike psoriasis, AGEP rarely affects the palms or soles. But here’s the catch: in community clinics, up to 40% of cases get misdiagnosed. It’s often mistaken for bacterial infections, psoriasis, or even allergic reactions. That’s why seeing a dermatologist matters.

What Causes AGEP?

Almost every case of AGEP is triggered by a drug. In fact, over 90% of cases are linked to medications. The most common culprits? Antibiotics. Specifically, amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin), macrolides like erythromycin, and other beta-lactams. These drugs account for about 56% of all reported cases.

Other frequent offenders include antifungals (12%), calcium channel blockers (8%), and even some anticonvulsants or NSAIDs. Even strange ones like intravenous iodinated contrast or herbal supplements have been linked. And here’s the twist: sometimes the drug that causes it isn’t the one you just started. A patient might have been on a medication for weeks, and AGEP shows up days after the last dose.

One of the most confusing cases involves corticosteroids. There are documented cases where patients developed AGEP after taking prednisolone. But then, in the same study, those patients were successfully treated with methylprednisolone. That means it’s not about steroids in general-it’s about specific molecules. This makes it harder to predict what’s safe to use next.

Genetics may also play a role. Research in Asian populations has found a strong link between AGEP and a specific gene variant: HLA-B*59:01. People with this marker are nearly 9 times more likely to develop AGEP after certain drugs. While not yet used in routine screening, this could change how we prevent AGEP in high-risk groups in the future.

How Is AGEP Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test for AGEP. Diagnosis relies on a mix of clinical signs, timing, and sometimes a skin biopsy. The EuroSCAR group developed a diagnostic scoring system called the AGEP Probability Score (APS). It’s not perfect, but it’s accurate-94% sensitive and 89% specific. It looks at things like:

- Time from drug start to rash (1-5 days)

- Number and pattern of pustules

- Fever above 38°C

- High neutrophil count in blood

- Normal eosinophil count (unlike some allergies)

- Positive skin biopsy showing subcorneal pustules

A biopsy is often needed to rule out generalized pustular psoriasis, which looks similar under the microscope but behaves very differently. Psoriasis tends to come back, often without drugs, and responds to different treatments. AGEP? It usually vanishes on its own once the drug is stopped.

That’s why the first step in diagnosis is always asking: “What new medication did you start in the last week?” Many patients don’t realize a new antibiotic or painkiller could be the trigger. Doctors need to dig deep-not just list current meds, but recent ones too.

How Is AGEP Treated?

The single most important thing you can do? Stop the drug. Immediately. In over 90% of cases, removing the trigger leads to full recovery within 10 to 14 days. No treatment needed. Just time.

But not everyone waits. Supportive care is standard: cool compresses, moisturizers, antihistamines for itching, and fluids if you’re running a fever. Some doctors recommend mild topical steroids to calm the redness. But here’s where things get controversial.

Should you take oral steroids like prednisone? Some experts say yes. A 2023 review of 15 international dermatology centers found that patients on steroids recovered about 3 days faster than those who didn’t. In severe cases-with over 20% of skin covered or high fever-steroids can reduce hospital stays and prevent complications.

But other experts, including a team from Baylor College of Medicine, argue against steroids. They say AGEP is self-limiting. Steroids don’t change the outcome-they just mask symptoms. And they come with side effects: blood sugar spikes, mood changes, bone thinning. One study of 15 patients over three years found no benefit from steroids, and all patients recovered fully without them.

So what’s the answer? It depends. If you’re young, healthy, and the rash is mild? Stop the drug and wait. If you’re older, have other health problems, or the rash is spreading fast? Steroids might help. The consensus? Don’t use them routinely. Use them selectively.

For the rare cases that don’t improve? New options are emerging. Biologics like secukinumab (a drug used for psoriasis) have worked wonders. One patient with AGEP triggered by amoxicillin didn’t respond to steroids. After one shot of secukinumab, their pustules vanished in under 72 hours. No infection. No side effects. It’s not FDA-approved for AGEP yet-but it’s being tested in clinical trials right now.

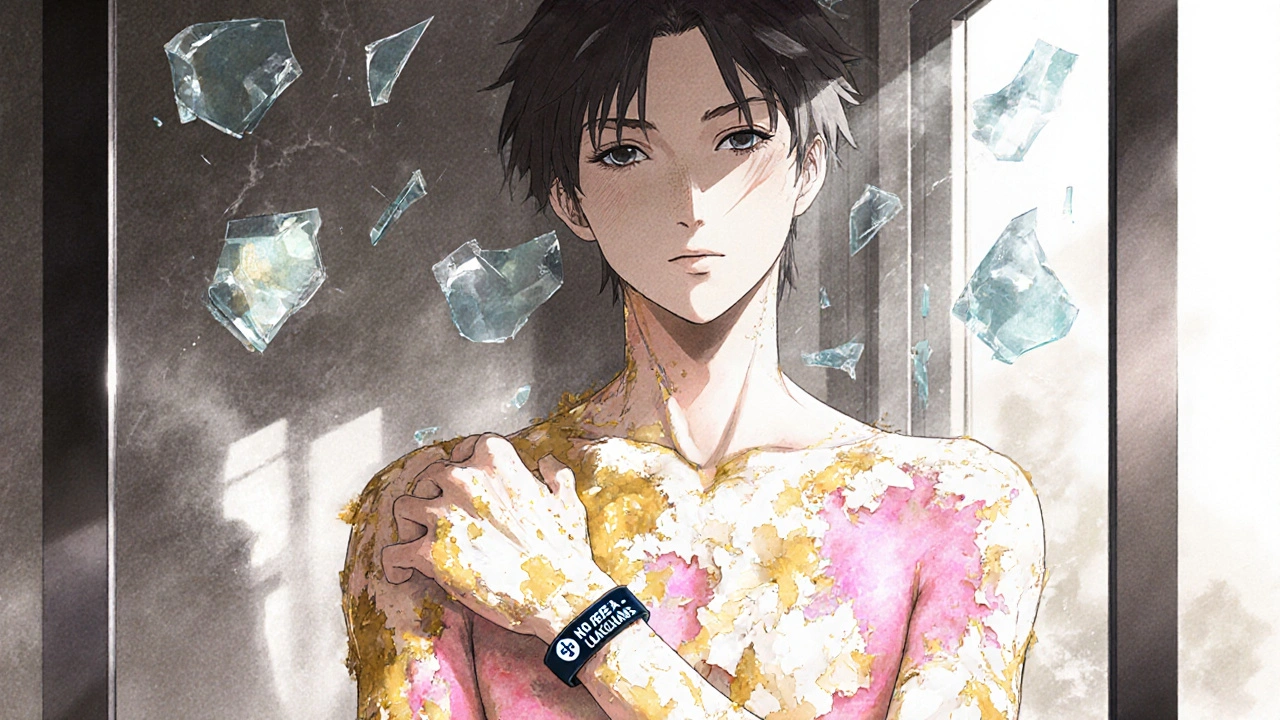

What Happens After the Rash Goes Away?

Once the pustules fade, your skin starts peeling. This usually happens around day 7 to 10. It’s not dangerous, but it’s messy. Your skin may feel tight, dry, and sensitive. Sun exposure can make it worse. That’s why patients need clear instructions: use fragrance-free moisturizers every day. Wear sunscreen. Avoid hot showers. Skip harsh soaps.

Studies show that patients given written instructions were twice as likely to follow them compared to those who just got verbal advice. Simple things matter. And they prevent long-term issues like dark spots or scarring.

Most people make a full recovery. The mortality rate is low-only 2% to 4%. That’s much better than Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, which kills up to 25% of patients. But recovery doesn’t mean you’re safe forever. You’ll never be able to take the drug that caused AGEP again. Ever. Cross it off your list. Tell every doctor you see. Put it in your medical alert bracelet if you have one.

What’s Next for AGEP?

Research is moving fast. The EuroSCAR group is rolling out a new diagnostic tool called AGEP 2.0, expected in early 2024. It’s more precise, easier to use in emergency rooms, and includes genetic risk factors.

Pharmaceutical companies are now required to monitor for AGEP in clinical trials for antibiotics and heart meds. The FDA and EMA both updated their guidelines in 2022 and 2023. Drug labels for amoxicillin-clavulanate now list AGEP as a known risk.

And biologics? They’re the future. IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors-drugs that block specific inflammation signals-are showing promise in early trials. One trial with secukinumab reported 92% success in treating resistant AGEP, with no serious side effects in 13 patients.

Soon, we might be able to test for genetic risk before prescribing high-risk drugs. Imagine a simple blood test before you start an antibiotic: “You carry HLA-B*59:01. We’ll avoid this class of drugs.” That’s not science fiction anymore. It’s coming.

What Should You Do If You Think You Have AGEP?

If you’ve started a new medication and suddenly develop a rash with white pustules and fever:

- Stop taking the medication immediately.

- Call your doctor or go to urgent care. Don’t wait.

- Take a photo of the rash. It helps doctors see how fast it’s spreading.

- Write down every drug you’ve taken in the last 2 weeks-even over-the-counter ones.

- Don’t try to treat it with creams or home remedies. This isn’t a typical rash.

Most cases resolve without long-term damage. But delay can mean longer hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotics, or misdiagnosis. Early action saves time, money, and stress.

AGEP is rare. But when it happens, it’s serious. It’s not something you ignore. It’s not something you treat yourself. It’s a signal from your body: something you took is triggering a dangerous immune response. Listen to it. Act fast. And remember-you’re not alone. Thousands of people have recovered from this. With the right care, so will you.

Yash Hemrajani

November 29, 2025 AT 06:30So let me get this straight - we’re now diagnosing a rash based on whether someone took Augmentin last week? And if you didn’t mention it, you’re just a walking misdiagnosis waiting to happen? Classic. At least the pustules don’t lie. Unlike my last PCP who thought it was ‘stress hives’ and gave me antihistamines like I was 12 and ate too much candy.

Also, HLA-B*59:01? That’s not a gene, that’s a warning label on a bottle of antibiotics. Someone’s gonna get sued for not screening for this. Mark my words.

Pawittar Singh

December 1, 2025 AT 02:33Yo, if you’re reading this and you’ve got a rash + fever after a new med - STOP IT. Like, right now. Don’t wait for your appointment. Don’t ‘wait and see.’ Your skin is screaming. I’ve seen people lose weeks of their life because they thought it was ‘just a reaction.’ You’re not allergic to penicillin? Doesn’t matter. This isn’t hives. This is your immune system going full SWAT team on your body.

And yes - take a photo. Text it to your doc. Even if they’re lazy. You owe it to yourself. 🙏

Josh Evans

December 1, 2025 AT 11:08My cousin had this last year after a Z-pack. She thought it was a heat rash. Took her 5 days to get to a derm. By then she was in the hospital. They gave her IV fluids, stopped the antibiotic, and she was fine in 10 days. No steroids. No drama.

Just… listen to your body. And if you’re on antibiotics, keep an eye out. It’s weird, but it’s real. And honestly? The fact that it clears up so fast once you stop the drug is kinda wild. Like your body just needed a reset.

Allison Reed

December 1, 2025 AT 22:06This is one of the most important posts I’ve read in a long time. Thank you for breaking this down so clearly. So many people think ‘rash = allergy’ and reach for Benadryl or hydrocortisone. But AGEP isn’t an allergy - it’s an immune overreaction. That distinction changes everything.

And the part about genetic risk? That’s the future. Imagine a world where your doctor knows your HLA profile before prescribing. We’re not far off. Keep pushing for this awareness. People need to know.

Jacob Keil

December 2, 2025 AT 04:39So drugs cause this but steroids can treat it? So the same class of chemicals that trigger it can also fix it? That’s not science that’s just chaos. Who designed this system? Who decided that the body’s immune response is a bug and not a feature?

And why are we still using antibiotics like candy? We’re not fighting bacteria we’re fighting ourselves. This is the cost of modern medicine. We fix one thing and break ten others.

Also I typed this on my phone so sorry for the typos. I’m too angry to care.

Rosy Wilkens

December 2, 2025 AT 07:16Let me guess - this is all part of the Big Pharma agenda. They know AGEP is rare, so they don’t warn you properly. Then they sell you expensive biologics like secukinumab to ‘fix’ what they broke. And now they’re pushing genetic testing so they can charge even more.

Did you know the FDA gets funding from pharmaceutical companies? Coincidence? I think not. They want you scared. They want you dependent. They want you on lifelong meds. This isn’t medicine - it’s a business model.

And don’t even get me started on ‘clinical trials.’ Who’s funding them? Who’s getting paid? You think they care if you live? No. They care if your insurance pays.

Andrea Jones

December 2, 2025 AT 16:54Okay but… the part about secukinumab working in 72 hours? That’s insane. Like, if a psoriasis drug can fix this in three days - why isn’t everyone using it? Is it just because it’s expensive? Or because no one’s tried it yet?

I’m not a doctor, but this feels like the future. We’re moving from ‘stop the drug and wait’ to ‘hit it with a precision missile.’ And honestly? I’m here for it. If we can stop people from suffering for two weeks when we can fix it in three days… why wait?

Justina Maynard

December 3, 2025 AT 20:53I’m not a medical professional, but I’ve spent the last three years obsessively researching drug-induced rashes after my sister got AGEP. She took amoxicillin-clavulanate for a sinus infection. Four days later, she looked like she’d been dipped in boiling sugar. The pustules? Like poppy seeds on fire.

They misdiagnosed her three times. One doctor said it was ‘eczema flare.’ Another thought it was chickenpox. The third? ‘Maybe you’re allergic to the pill’s dye.’

She had to go to a university hospital to get it right. And now? She carries a card in her wallet. It says: ‘DO NOT PRESCRIBE BETA-LACTAMS.’ I wish every patient had that. Because no one should have to learn this the hard way.

Evelyn Salazar Garcia

December 4, 2025 AT 18:21So we’re supposed to stop all antibiotics now? Great. Now we’re back to the 1920s. People die from infections. This is why America’s healthcare is broken. Too much focus on rare rashes, not enough on saving lives.

Also, why is this even a thing? Shouldn’t drugs be tested better? Or is this just another American overreaction to something that barely happens?

Clay Johnson

December 5, 2025 AT 04:38Drug triggers immune response. Immune response kills rash. Steroids suppress immune response. So steroids treat the symptom not the cause. But the cause is the drug. So stop the drug. End of story.

Genetics? Interesting. But not necessary. The drug is the trigger. Not the gene. The gene just makes you more likely to react. Like a lightning rod. Not the storm.

Biologics? Maybe. But expensive. And unproven. For now - stop the drug. Wait. Let the body heal. That’s all.

Jermaine Jordan

December 5, 2025 AT 10:44Imagine waking up and your body has turned into a battlefield. Tiny white grenades exploding across your skin. Fever. Swollen lymph nodes. You can’t even touch your own arms without wincing.

This isn’t just a rash. This is your immune system going nuclear. And it happens because you took a pill for a sore throat.

That’s the horror of modern medicine. We’ve created a world where the cure can be worse than the disease. And yet - we still reach for the bottle. We still trust the label. We still don’t read the fine print.

But now? Now we know. And knowledge? Knowledge is the only thing that can save you.

Chetan Chauhan

December 5, 2025 AT 20:52Wait hold up - you’re saying amoxicillin causes this? But in India we give it to kids for coughs like it’s candy. No one gets this. So either it’s not real or it’s a Western problem. Or maybe you’re just overdiagnosing.

Also HLA-B*59:01? That’s a South Asian gene? I thought it was only in Japanese people. Did you even check the data? Or are you just copying some US study?

Also I typed this on my phone and I think I misspelled ‘pustules.’

Phil Thornton

December 6, 2025 AT 21:02My mom got this. She took a new painkiller. Two days later - pustules. Fever. Panic. We went to the ER. They didn’t know what it was. She was there for 48 hours. Then a derm walked in, looked at her, and said ‘AGEP.’

Stopped the drug. She was fine in 10 days.

Now she won’t take anything without checking with me first.

Just say no to random meds.

Pranab Daulagupu

December 8, 2025 AT 20:49AGEP is a rare but critical immune-mediated reaction. Beta-lactams are primary triggers. HLA-B*59:01 confers significant genetic susceptibility. Diagnosis requires clinical correlation with biopsy confirmation. Management hinges on prompt drug cessation. Steroids remain controversial but may reduce morbidity in severe cases. Biologics like secukinumab show emergent promise in refractory presentations. Long-term avoidance of the offending agent is mandatory. Patient education improves adherence and reduces recurrence risk.

Barbara McClelland

December 9, 2025 AT 20:25Okay, real talk - if you’ve ever had a rash after a new med, even if it seemed ‘mild,’ you need to write it down. Not just in your head. Not on a sticky note. In your medical record. Tell your doctor. Tell your pharmacist. Tell your family.

And if you’re a parent? Don’t let your kid take antibiotics without asking: ‘What are the red flags?’

You don’t need to be a doctor to save a life. You just need to be loud enough to be heard.